One of the world's most enduring and misleading myths is that we can, and should, control other people; and that other people or events can control us.

The myth is an enduring one because it is nurtured into us from childhood, embedded in our language and propagated by our media.

It's a convenient myth. It enables us to blame others and complain constantly. We can use it to excuse ourselves whenever it's convenient: 'he made me do it', 'I had no choice!', 'it's their fault!

We all respond negatively, usually with resistance or resentment, when we perceive that we are being controlled by others. Yet we still accept the idea of external control so strongly that we unthinkingly adopt the language of the behavioural scientists of the last century. They persuaded us that 'positive reinforcement' is necessary for learning and that 'negative reinforcement' is important for discipline.

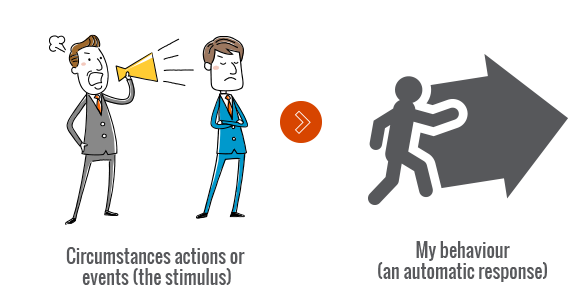

The behaviourist hypothesis is that there is nothing between the 'stimulation' of events outside ourselves and the behaviour we respond to. They formulated this hypothesis by observing the behaviour of rats in artificial conditions and then generalising their findings to humans. They never did any work on humans!

What they propose can be diagrammed something like this:

Because the laboratory researchers could observe nothing between the stimulus they applied and the rats' responses, they concluded that there was nothing.

There is no behaviour we can choose (no stimulus we can apply) that will cause a predictable response in another person.

If the myth was reality, then our brains would work something like this: whatever happens outside us would be simply a stimulus (a prod) which generates a behaviour. That's why it is called stimulus-response theory. Controlling other people would simply be a matter of choosing the correct 'prod' and they would obey our wishes.

Now when we put it like that, the myth starts to look a bit exposed. Anyone who has tried to stop an infant's tantrum or persuade a rebellious teenager, will know that there is no behaviour that we can use that will cause a predictable response in another person. What works in a laboratory, using tied-up dogs or rats in a maze, doesn't seem to work at all in the complicated world of humans.

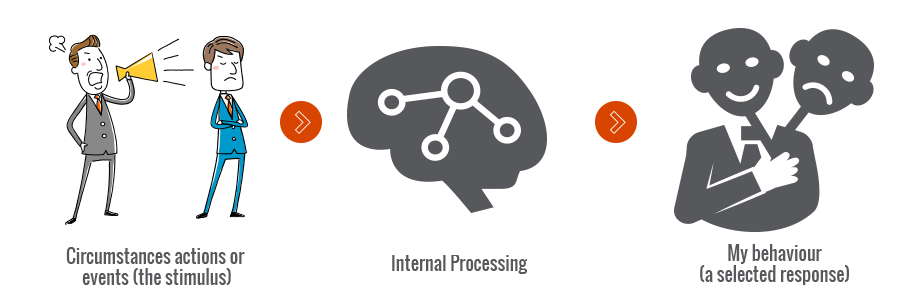

What actually happens with humans can be illustrated like this:

The internal processing is not just something we hypothesise – it is what we experience. It may not be visible on the outside but it is very real on the inside!

This internal experience to threats, punishments or attempts to control us with rewards generates an internal response that ranges along the scale from compliance to resistance.

When we are compliant, when we go along with what another person wants us to do, it is simply because we make an internal choice to avoid the pain of punishment or decide to accept the reward. When we resist it is because we want to make a different choice, we are not prepared to go along with what the controlling circumstances or person wants.

Some kids are very compliant – they make it seem as if external control works. Other young people never respond to our prods and pushes and seem wilfully determined to defy us. We call their actions 'misbehaviour' and re-double our attempts to control them. The more we do it the more pain we create and the more the relationship with them is damaged, but once we have in our heads the insidious mantra of external control – 'I know what is right for you and I must force you to do it' – we find it difficult to let go.

When we try to control other people, whether we seem to succeed or not, the relationship is put at risk!

The simplicity of the 'quick fix' is what makes external control so attractive. When someone is doing something we don't like, we use threats, pain or reward to control them. But even when it works in the short term, the consequence is that there is long term damage to relationships. And the reason that the relationship is damaged is that we are not like experimental animals. As we know, there actually is something happening on the inside of us that separates the stimulus from our response.

Because we have our own internal wants, including a very strong urge to be autonomous, the feeling of having another person imposing their will on ours is never pleasant. We can go along with other people's control whenever we feel it is in our own interests, or when we figure out that it's just not worth the pain of resisting, but we never enjoy it. Being controlled always comes with its own frustration.

When people persistently attempt to control us, our internal frustration turns to resistance and then to resentment, both of which are damaging to the relationship with the person attempting to control us. The irony is that if we can't be externally controlled, we can only be influenced, and when the relationship with another person is damaged by their attempts to control, their influence is reduced.

External control may seem to work in the short term, but it always reduces influence in the long term.

Rob Stones is a Senior Faculty Memebr of the William Glasser Institiute. See more info at

Choice Theory