Free Resources

Free Resources

Acquiring the Habit of Resilience

Resilience is the ability to manage the difficulties in our lives calmly and capably. It’s such an important life skill because we all have difficult lives. Although we all have times of joy and satisfaction, challenge, anxiety, grief, disappointment, and pain attend every person’s experience. None of us is free of them.

What we can do is learn to deal with these inevitable difficulties without being damaged or distracted by them. And because we encounter painful setbacksboth frequently and unexpectedly, acquiring the habit of resilience means that we are always prepared.

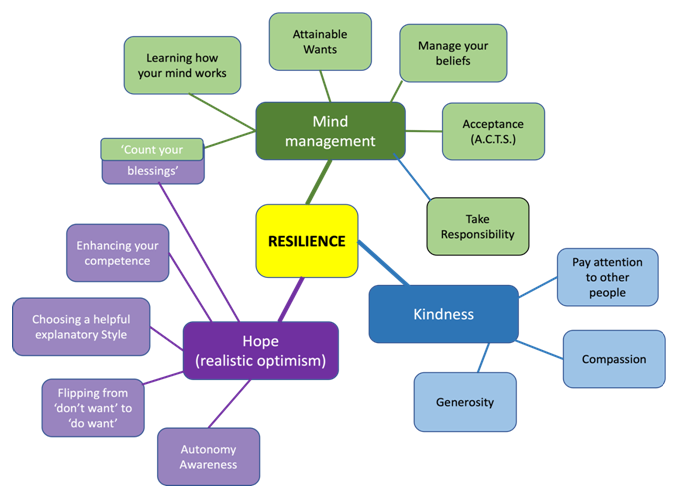

This resilience mind-map illustrates a mosaic of habits that you can acquire to bolster your own resilience:

The number of items in the mind-map can seem overwhelming but that is because the three main dimensions of resilience are broken down into some very specific habits that you can learn. You don’t need to learn and apply all of them. Your resilience will immediately improve if you choose one strategy from each group of habits and work on those. Obviously, the more of these helpful habits you can acquire the better.It’s important to regard acquiring the habit of resilience as a long-term project. There is no single instant fix that will reduce your vulnerability and bolster your resilience.

The resilience habits can be broken into 3 groups:

Managing your Mind

Managing your own mind is more than present-moment awareness. It does involve:

- Understanding how your own mind works.

- Managing your own perceptions with helpful self-talk.

- A.C.T. – Accepting the Situation. Choosing what to do next. Taking action.

- Making sure that what you want is attainable.

- Create a routine way of counting your blessing: noticing what is going right.

Becoming more Hopeful

- Explaining both good and bad events to yourself in a helpful way.

- Whenever you are thinking about a ‘don’t want’ flip it to what you do want.

- Continue to develop yourself and improve your competence.

- Making sure that what you want is attainable.

- Nurture your own autonomy – you are not dependent on other people.

Practising Kindness

- Being kind to others and both feeling and showing compassion for them, bolsters your own resilience.

- Pay attention to other people. Moving the focus away from yourself brings balance to your life.

- Practising Generosity

Before we explore these in detail, let’s understand why habituating these ways of thinking and responding to the world is so important.

The habit brain supports resilience

Our brain is designed to turn every behaviour into a habit. When we learn something, we learn to repeat it, not just access it once. In that way we automate everything. When we learn a behaviour or a skill, we don’t have to repeat it consciously. We learn to do it unconsciously.

Once we have learned a skill or acquired a behaviour, the associated neural connections are wired together. We don’t have to invent the sequences of mental threads needed to dance or swim, plan a route, or solve a problem every time we need them. Through repetition, the brain learns the neural recipes we need.

Resilient responses need to be habituated too. Otherwise, whenever stress or pain loomed across our lives, we would have to create a new way of managing them every time they threated.We would be easily overwhelmed if a resilient response had to be invented eachtime we needed one. We are more buoyant when we make resilience a habit.

Responses to Habituate

Resilience Strategies in Detail

Managing your mind

Mind Management 1: Understanding how your mind works

It’s hard to manage your own mind if it is a mystery to you. Knowing even a little about how your mental processes work can help you feel in control.

Your mind is constantly comparing what you want with your perceptions of what is happening and trying to close the gap between the two. That means that we are more likely to notice what is wrong than what is right!

Understanding this has two advantages:

Firstly, it helps us to understand why our lives are so rarely perfect. It’s easier to be resilient when we are not surprised by the imperfection of life. Expecting challenges, we are better prepared to deal with them.

And

Secondly, we can learn to balance this by noticing what is going well. Because this is not natural, because the brain naturally attends to what’s wrong, acquiring the habit of noticing the positive requires work – but it rewards us. Taking Grandma’s advice to ‘count our blessings’ actually does contribute to our resilience.

(For more on mind management read the Choice Theory page).

Mind Management 2: The habit of acceptance

Accepting what is or what has happened is essential to resilience. Wishing things were different or resenting what has occurred erodes our resilience.

None of us can change things once they have happened. We don’t have a time machine to jump into so that we can go back and fix things. Going over and over what happened in the past just means that we re-live painful events of circumstances over and over again.

The habit of A.C.T. liberates us from the pain. A.C.T. is a great habit to develop.

A – Accept what has happened. It is the reality.

C – make choices about what happens NEXT. We can’t change the ‘before’, but we always have some choices about what to do next.

T – Take action. Whatever you choose – DO IT. When we take action we feel in control, which always feels better than being passive and letting things happen to you.

Accept the situation.

Whatever happened, or is about to happen, accept what cannot be changed. Especially accept that you, like every other persona is less than perfect. You miss opportunities and sometimes neglect the things that your best self would take action on. In the same way accept what others have done.There is little point in blaming, complaining, or making excuses. None of us have a magic wand that enables us to go back into the past and make changes. What is done is done. Accepting the situation liberates us to move on.

Consider the CHOICES you DO have.

Once the situation, is accepted you canconsider what choices you do have. In some situations, the only choice we have is to ask for forgiveness, forgive yourself, and to do your best to make things right from this moment Never fudge it or pretend. Choose whatever will work best to make things right.

In other situations, when other people or events have brought us pain, accepting whatever has happened is the key. If we can improve the situation though our own choices, we should. If not, we still have choices, opportunities to mould our own future and influence what happens next. As Victor Frankl observed: 'Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the answer to the problems it presents.' Life does present problems but always presents choices.

Take Action.

Decisions are only really made when action is taken. Whatever you choose to do, either do it at once (if that is possible), or else make a clear plan of when and how you will take action. Intentions are never enough. Many people form intentions but don't take the next step. They allow themselves to be paralysed by their own negative self-talk and then delay, put off and find reasons not to act. Take action, even if it is does not work out perfectly. Mistakes are the foundations of learning.

As a habit, A.C.T. equips us to move on. When something bad happens, we deal with it and take control.

Mind Management 3: Managing your negative perceptions

We don’t perceive the world as it is. We perceive it as we are. Our perceptual system is not a window, it is an interpreter. We translate whatever happens through our own values and beliefs and through our prior experience.

Albert Ellis used this knowledge in developing Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Because the human mind translates activating events (A) through our existing beliefs (B) the emotional consequence (C) is often the result of the belief we bring to the event, not the event itself. And very often because the belief is negative or self-limiting, the emotional consequence is that we feel ‘down’ or out of control.

Ellis encourages us to add ‘D’ and ‘E’ to our perception Alphabet. Instead of being disturbed by our beliefs, we can learn to dispute them (D) the limiting or disquieting belief and choose a more helpful one - so that we view the world through a more effective (E) lens.

It’s important to be clear about what a belief is. It is simply a perception that we have elevated to the status of a ‘fact’. We do this whenever we think a perception is a reliable and helpful way for us to view the world. A belief is a perception that we have come to depend on as we navigate our way through the world.

However, when a belief is no longer helpful, we should abandon it. It no longer serves us. Beliefs that discourage us, that limit us, or that discourage us from action or commitment are not helpful. As ‘Ellis’ says they are ‘irrational’. It cannot serve our rationality to be stopped by a perception, however much we have been inclined to trust it in the past.

Mind Management 4: Choosing attainable wants

Reaching for the stars is good for us – until it’s not!

Although it’s healthy to set goals - and having challenging goals and working towards them actually supports our resilience, but this needs to be balanced with a certain amount of realism.

I have written elsewhere about my youthful yearning to be a world-class sprinter. I strove for this goal for years but made little progress. Eventually, I became discouraged. It took me a long time to admit to myself that I did not have the physiology to achieve my dream. Specifically, I did not have the pre-ponderance of fast-twitch muscle fibres needed for running very fast. Persistent discouragement erodes resilience and can often lead to emotional fragility.

Sensibly I chose a new ‘want’, a new ideal or goal for myself. I chose to become a successful long-distance runner and set myself a new goal, a more attainable one. I decided that my new ‘want’ was to be a World Champion Marathon runner. It was possible: attainable. I did not actually succeed but I achieved enough to keep the dream alive for many years. That process of striving and making progress supports our resilience.

The literature on setting goals that support our mental health emphasises that our goals should be SMART. The A stands for attainable. (The other letters in the Acronym are Specific, Measurable, Realistic and Time-framed).

To build your resilience, a sense of progress is important: a sense that there is movement in our journey. To support our resilience, we should choose attainable wants.

Mind Management 5: Count your blessings

One of the surprising inclusions in the US army ‘Master Resilience Training’ program designed by Dr. Martin Seligman was the ‘3 blessings journal’.

Throughout the program, the US Army Sergeants who participate in it keep a gratitude journal, in which they record all of the good things that have happened, and that they have noticed about other people, in the preceding day.

Seligman describes this ‘Hunt the Good Stuff’ practice as an important way to enhance positive emotions. He writes: “Our rationale is that people who habitually acknowledge and express gratitude see benefits in their health, sleep and relationships, and they perform better.”

Seligman notes that the hard-headed, pragmatic NCO’s of the US Army valued and openly expressed a high opinion of this rather simple strategy.

The counterpoint to this is that people who focus mostly on counting their afflictions, on spelling out the awfulness of their work lives, on noticing everything that is wrong, are far from resilient. Allowing their emotions to be the plaything of whatever problems they perceive, they are susceptible to hopelessness.

The message here is clear. We bolster our resilience by counting our blessings, noticing what is going well, appreciating those who are doing the best they can, expressing that appreciation without reserve.

Mind Management 6: Take Responsibility

One thing we know about our own mind is that we are the only person who has access to it. Mind is the awareness that springs from the brain’s energy. Both mind and brain operate inside the bag of skin we call self.

Now we often don’t think about it quite like this. We often think and talk about being ‘made to do’ things by other people or events. From early in our childhood, we often acquire the habit of blaming other people or difficult circumstances for our responses, as if something that someone did or said ‘caused’ our response.

The reality is that all we get from the world around us is information. This information comes to us via our senses: through what we see or hear, taste, smell of touch. These are the five portals through which we access the world around us, and we always choose what to do with the information we take in.

Of course, there is always a great deal going on around us. Sometimes these external events will seem to us to be pleasurable, helpful or life-enhancing. At other times, other people or events will appear to be threatening, painful or inhibiting. What we can notice though, is that being pleasurable or painful is not a quality of the perceptions we take in, it is how we value those things.

That’s not to deny that there are circumstances that we experience as painful. Most of us experience grief or fear when things seem to be going badly wrong. However, it is always true that the strength of these feeling responses is very individual. Even more noticeably, what gives pleasure is very often wildly different. I am fearful of heights, violence, and guns, but around the world these are millions of people who are thrilled and excited by those things.

Now, it makes a vast difference to our resilience if we accept that we are responsible for all of our behaviours. No matter what happens if I think of myself in control of my response, of what happens next, I will be far more resilient than someone who believes that they are a helpless victim of circumstances.

Developing the habit of taking responsibility for what happens next, whatever the cause of the troubling circumstances in the present, is a resilient response.

Nurturing Hope

Nurturing Hope 1: More on 'Count Your Blessings' - Be Grateful

At every turn we have a choice to hope or to feel hopeless. They are the two faces of every new moment in the life of a human. We are always wondering or fearing.

Both attitudes take about the same amount of effort, and both are nurtured by how we view our past experience.

When we dwell on the distress we have encountered and fear that each new step will take us there, we will inevitably be drawn into that abyss. When we choose instead to fill our thoughts with gratitude and count the moments of blessing and the joys of opportunities taken, then these will tend to permeate our expectations and fill our lives with hope.

Nurturing Hope 2: Choose Helpful Explanations

How we explain events to ourselves influences our resilience. If we tell ourselves that the occurrence of something bad means that it shows we are weak, it will have long term implications, and it will always be like this, we are explaining the difficulties we encounter pessimistically. It is hard to be resilient if we explain things to ourselves like this.

In his book ‘Learned Optimism’, Martin Seligman describes the two different ways in which we can explain what happens to us. As implied by the title of his book, Seligman argues that we can learn to be more optimistic if we challenge our pessimistic beliefs and the associated self-sabotaging habits.

The way we talk to ourselves about situations and events is significant. If we explain good events as if they were lucky accidents beyond our control, we can easily feel that we are lost in a world outside our control. If, on the other hand we see the same good events as due to our own efforts and likely to continue we develop a robust self-belief that will give us confidence when faced with challenges.

Perhaps even more significant, the way we talk to ourselves when we are challenged is pivotal. Faced with difficulties telling ourselves that ‘these things always happen to me’ and attributing the situation to own lack of competence or control, we are likely to tell ourselves ‘I can’t deal with this’ or ‘this is too hard!’

Changing the way we talk to ourselves, from self-limiting to helpful, is a matter of deliberately noticing and addressing the specific ways we talk to ourselves. Turning ‘I can’t’ into ‘I can’ or perhaps ‘I can’t yet’ can begin to transform the way that we regard obstacles. Replacing the pessimistic ‘Situations like this always overwhelm me’ with ‘I have successfully managed these kinds of situations before’ transforms our ability to deal with challenges.

Optimists resist helplessness and do not give up when faced with problems that initially seem insurmountable. Optimists are resilient because they have learned to tell themselves that they can find a way. Of course, their optimism has to be tempered with realism. Not facing real problems simply delays dealing with them. As Seligman writes, Realistic Optimists are the most likely to be resilient.

Being realistically optimistic does have to be learned if it is not our natural inclination. Once we learn to challenge unhelpful beliefs, we can try out new ones. We do have tools with which to challenge our pessimistic and limiting beliefs. Both Ellis’s ABCDE procedures and the kind of Reality Thinking that you will find elsewhere on this website will help you with procedures that help you challenge pessimistic ways of explaining thigs to yourself.

Nurturing Hope 3: Flip to the Positive

It does not serve our resilience to spend time thinking about what we don’t want.

It’s a common habit. Thinking ‘I don’t want this to happen’ or ‘I hate it when people behave like that’ is a statement of the problem but never advances us towards a solution.

Learning to reframe or re-state the problem situation by identifying what we do want rather than lingering on what we don’t want is liberating. Judy Hatswell describes this a ‘flipping’. Not a scientific term but a useful one. She teaches that every negative perception is painful because it is the opposite of a pleasurable situation that we would much prefer. Every don’t want is a negative way of revealing that things are not as we would like them to be. The secret of flipping is to focus how we would like things to be. We can then use ‘Reality Thinking’ to work out the behaviours that will take us to what we do want.

This is quintessential resilience. When faced with a problem, search for the solution. In every life situation there are problems. The resilient response is to search for solutions – and the first step in this process is believe that we can.

You can help yourself by using the table below to practice with. On the left are common statements that emphasise limitations. On the right are the positive alternatives.

| We are avoiding the negative perception of being: | What we want is to perceive ourselves as: |

|---|---|

| Frustrated, incompetent, failing, fragile, unsure, weak, unsuccessful, unimportant. | Capable, competent, confident, skilled, respected, effective, strong, important. |

| Lonely, left out, isolated, rejected unwanted, friendless, mistrusted, abandoned. | Loved, cared about, cared for, included, liked, connected, befriended, friendly, trusted. |

| Coerced, constrained, limited, obstructed, restricted, unwilling, dependent. | Free, in-control, autonomous, independent, willing, self-sufficient. |

| Bored, weary, uninterested, ignorant, foolish, unintelligent, unsuccessful, defeated, exposed. | Learning, growing, developing, curious, joyful, inspired, challenged, achieving. |

| Fearful, anxious, scared, threatened, intimidated, bullied, vulnerable, insecure, endangered. | Safe, secure, confident, protected, trusted, hopeful, courageous, determined, resilient. |

The key thing is to remember the old saw that whether you think you can, or you think you can’t, you will be right. It’s our self-belief that enable us to respond resiliently.

Nurturing Hope 4: When you can't learn how. Enhance your own competence.

Hand in hand with our self-talk is our readiness to enhance our effectiveness. Our progress and achievements are often held up by the things that we have not learned to do -yet! - or by the things we don’t know enough about- yet!

Hand in hand with resilience goes the will to grow our capabilities to manage the situations that we encounter as we live. Willingness to transcend our present level of competence and learn new skills contributes to the growth of hope as well as the management of our mind.

Learning supports our resilience by helping us feel good. Learning gives us access to dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is the body’s own pleasure drug. With the thought ‘I can learn this’ we release a little spurt of dopamine into the brain – an encouraging dose of feel good. Then, as we learn and increase our proficiency, we give ourselves even more dopamine shots to reward ourselves. Being a lifelong learner is an enormous boost to our resilience.

Of course, our own self-talk is vital to this. Refer to the previous section on flipping and you will see hoe these two key pieces of the resilience jigsaw are related. If my inner dialogue is focused on ‘I can’t do this’ our inner bounce is inevitably diminished. If we flip to ‘I have not learned this yet’ the assumption that it is learnable draws us on. The moment I say to myself’ I can learn this’ the encouraging effect of the dopamine system gives us a sense of well-being.

Nurturing Hope 5: Rejoice in your own Autonomy.

Things may be far from perfect in the world, but we can be grateful that we have a natural shield – if we understand it and care to use it.

The human mind is a control system. We manage our lives and make choices about what to do next through conscious mental activity or non-conscious brain activity. All of this happens inside us, inside the bag of skin we call self. Nobody can reach inside that sealed container to manipulate our mind or brain (except a surgeon). We are an internally controlled system.

Now it often does not seem like that. Our containers does have ‘windows’ that connect it with the world outside us. Through our capacity to see and hear, to smell and taste and feel we are connected to the world around us even though we are separated from it. Around us, the world is full of information. We take in this information through our senses and interpret this sensory information and giving it meaning. This happens inside us.

All that means that we have the capacity for independence, to make choices whatever is happening in the world around us. There may be difficult or painful events happening,but we make the decisions about how to respond inside ourselves.

Practising Kindness

One of the surprising findings from studies on resilience is the importance of kindness, empathy, and generosity. However, when we look at what is common to the attitudes and practices that are related to kindness and empathy we should not really be surprised. There is a common thread in these attitudes: a willingness to look beyond ourselves as we live and work in the world.

Vulnerability and despair, those states that threaten our resilience, are strongly associated with our tendency to turn inwards when we are under pressure. When that happens, it is easy to think that we are victims of the world’s vicissitudes and the slights of others.

Turning outward, attending to and caring about others is the antidote.

Practising Kindness 1: Pay Attention to Others

In the construction of a life of contentment, a focus on self alone is damaging. Although we can only control our own behaviour and we are responsible for our own resilience an unrelenting self-focus can damage our ability to keep things in perspective. When we focus entirely on what is right or wrong on our own world, it is all too easy to be preoccupied about what is less than ideal.

Recognising the common threads of a human life, the threads of pain and difficulty as well as joy and happiness, keeps us in balance. The world does not revolve around us alone. Thinking and behaving as if it does, skews our sense of the rightness of things.

On the other hand, ‘receiving, giving, or even witnessing acts of kindness increases the production of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood. Acts of kindness help build support systems which are crucial during challenging times and further boost our resiliency. Kindness fosters a caring community and the sharing of resources, as well as bringing purpose and meaning to life’ (The Science of Kindness, Cedar-Sinai Hospital).

Being able to adopt the habit of seeing things in ‘Second Perceptual Position’, from the perception of others, is one of the mind tools that will support our ability to do this. Instead of viewing circumstances and events from our own self-interest, making a conscious effort to pay attention to what is going on for those around us, changes how we see the world.

Second perceptual position is more than listening. It is paying attention to what is happening outside us instead of the disturbance inside. It requires us to combine what we are seeing and hearing from other people, with our intuition about what this means for them and what is going on in the world of their existence.

Adopting the habit of asking ourselves about what is going on in the lives of our colleagues, family and friends and seeing things from their perspective, trying to walk as if in their shoes, means that our attention takes us out of the world of self-obsession.

To read more about the Perceptual Rositions, follow this link to the resources area.

Practising Kindness 2: Pay Attention to Others

Empathy and Compassion are the twin dimensions of the attitude that take us out of our own concerns and enable us to apply that viewpoint to others.

As Daniel Goleman point out there are several kinds of empathyThe kind of empathy that builds resilience is the ability to recognise, understand and care about the feelings and thoughts of another person. Once again, this sense of reaching outside ourselves supports our resilience in two ways:

We acquire a greater understanding of the commonality or tough experiences. Understanding that our own challenges are an integral dimension of all human experiences takes the ‘why is this happening to me’ thought out of the equation. With this understanding we no longer think ourselves as a victim, having this pain specially inflicted upon us. Instead, we come to view our own challenges as normal and hence manageable.

Extending our empathy to others, and supporting them through their difficulties, provides us with the ‘helpers high’, a squirt of energising dopamine that supports our mood and bolsters our resistance.

Compassion and empathy are closely linked. Compassion brings sympathy and understanding to someone else’s plight. When we view another person’s circumstances with compassion, we display both tolerance and mercy to our view of their condition. Instead of being critical of their reactions and choices we respond with sensitivity to their difficulties.

Crucially, this habit of withholding criticism and extending compassion and understanding tends to spill over into our thoughts about ourselves. We can use self-compassion to manage the inner critic that undermines our resilience.

Few things challenge our resilience so insidiously than our own critical self-talk. One estimate from the USA National Science Foundation estimates that the average person has up to 60,000 thoughts per day. Of those, 80% are negative and 95% are exactly the same repetitive negative thoughts as we had the day before.

The way to manage these thoughts is not to fight them but to accept them. Feeling the same compassion for ourselves as we would for a friend inflicted by the same self-doubt and inner negative commentary takes the sting out of our thoughts.

If self-criticism is so much a part of human cognition, then thinking about ourselves with understanding and forbearance is much more useful than beating ourselves up for not being perfect. If we accept our own inner critic as part of being human we can practice the ACT protocol described above and also located in the resources section of this website.

Practising Kindness 3: Be Generous

Khalil Gibran defines generosity as giving more than you have. That is pretty close to the dictionary definition which is: ‘Giving more than is necessary or expected.’

Generosity is the hallmark virtue of those who look outside themselves; who pay more attention to the needs of others than of themselves. When times are tough, or when we are experiencing more adversity than usual, looking inward, and perseverating about how bad things are and how helpless we feel erodes our resilience. Looking outside ourselves and thinking about how we can help and support others, even when we are experiencing our own setbacks, bolsters our strength and flexibility.

Studies into the way communities rally around in the face of disaster show that everyone benefits from a generous attitude. Those who respond by reaching out to others and give their time and energy to supporting their neighbours recover far more quickly and suffer less trauma than those who withdraw into themselves.

Some practical ways that we can acquire the habit of generosity:

- Sharing what we have with those who have less.

- Working collegially rather than competitively.

- Regularly giving up our time to assist others (Not so much our money – donating is helpful but unless we give until it hurts us it does not seem to be so powerful as giving up our time and energy)

- Volunteering to work on organisations that support community members or those in need.

- Helping and coaching colleagues and friends.

- Giving encouragement to those who are struggling.

- Looking around our circle of friends and colleagues and actively identifying those who need a boost.

- Getting you own power need met by empowering others.

Generosity is a rewarding virtue. It gives back to the giver.

The Resilience Habits - A Summary

By adopting the habits and perspectives described above, you can cultivate resilience and effectively navigate life's challenges.

Remember, resilience is a continuous journey, and each step you take towards acquiring these habits brings you closer to a more resilient and fulfilling life.

None of the resilience habits can be acquired by wishing. Wishing is often a doorway to despair. Resilience is constructed through doing, by taking action. Identifying the habits that you want to acquire, learn, and practice each of these habits, one by one, and your resilience will grow.

Remember that the biological brain runs our lives by making a habit of everything. When we learn anything, the brain begins the creation of synaptic pathways that make everything automatic through repetition. When we begin to learn any behaviour, whether it is an action or a way of thinking, it is hard to begin with. The synaptic pathways have not yet formed. Every step forward must be made by conscious effort. Only with practise and repetition do we form the habits that make things easy.

When we acquire the habits we need to manage our mind, a hopeful attitude and choose to be kind to ourselves and others, we can live a resilient life. It will not be, cannot be, a life free of troubles. Life is difficult for everyone. However, with the habits of resilience we can acquire the ability to ‘meet with triumph and disasterand treat those twin imposters just the same”.1

1 From ‘IF’ by Rudyard Kipling.